[ad_1]

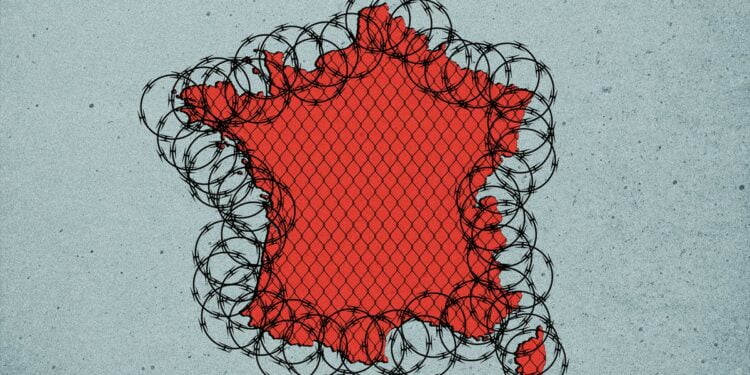

Ferreira was part of a growing movement of French youth drawn to a rebranded radical right that was—and still is—embodied by Le Pen.

What captured Ferreria’s imagination was how Le Pen talked about France. “It was that, for once, we truly spoke of France, the grandeur of France, because the other political parties have a tendency to say that France doesn’t exist, that it has no valor, no traditions. So the National Front taught me—me, I was born in France!—that, in fact, France exists, that France has always been here but France is sleeping and it’s necessary to wake it up. And it’s this, really, that truly fascinated me: that for once there was a party that was really rebuilding France for the French.”

When Ferreira turned 18, voting for the National Rally was a defining moment, the concretization of almost a decade of intrigue. She joined the party’s youth wing, then called National Front of the Youth and now known as Generation Nation. Ferreira didn’t know anyone when she signed up, driven not by social pressure or a search for community but by the interest she’d fostered on her own since childhood. Upon joining, however, she quickly found those benefits anyway: a full calendar through the youth wing’s myriad activities, with campaigning, meetings, and social events.

When I met Ferreira in May 2018 at a cafe in the heart of Paris, minutes from Notre-Dame Cathedral, she was 21 years old. She showed up with a friend, then-24-year-old Nicolas Gautier, another Generation Nation member who studied law at University of Paris 8. He shared many of his friend’s experiences and opinions: an attraction to the ways in which the party stood out from its more mainstream counterparts; a motivation to join despite not knowing anyone in the party and not coming from a right-wing family; perceived biases against the party from the education system and the media; worries about harassment at school; a steadfast faith in the narrative that the National Rally has successfully transitioned from a fringe protest party to a respectable, professional one; and a sense that most students in Paris are not, in fact, left-wing—just apolitical and quieter than their left-wing peers who, as they saw it, attracted outsized attention by barricading buildings and doing a lot of shouting.

The next generation of the French radical right lives outside of the stereotype of National Rally voters.

All of the major political parties in France have youth wings, but the National Rally remains particularly concentrated on attracting young people, training them, promoting them to leadership positions, and encouraging them to run for office. It does this with an eye towards expanding its base and recruiting youth like Ferreira and her ambitious, well-educated peers in and around Paris—a population usually thought more likely to sympathize with the students of 1968 or the people who took to the streets to protest systemic racism this summer than with a party best known for anti-Semitism, nationalism, and xenophobia. But the next generation of the French radical right lives outside of the stereotype of National Rally voters as rural, less educated, older, and male. Instead, many of its dedicated organizers and future leaders reside in universities at the center of a city widely associated with protests, strikes, and revolution, antagonizing that centuries-long history from the inside.

On a warm afternoon in May 2017, a group of students gathered to pass out flyers at Marché Saint-Eustache, a farmer’s market near the Louvre Museum. Nicolas was 23 and from the Pas-de-Calais region in northern France. He’d come to Paris to study at the Paris Institute of Political Sciences, one of France’s elite grandes écoles. He wore white pants, a burnt-orange turtleneck, and a blue blazer, a messenger back hanging over his shoulder; most passersby glanced at his flyers and kept walking. A man took one from Euryanthe Mercier, a 22-year-old communications student at the Sorbonne. He returned seconds later to give it back, having finally looked down to read it. “That’s your right,” she told him. Pausing to pose for a photo, the students held up flyers with Le Pen’s profile, “Eradicate Islamist terrorism” written in bright white letters.

They also expressed blatantly nationalistic and Islamophobic views, remnants of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s party that remain hallmarks of the National Rally today.

Founded in 1972 by Jean-Marie Le Pen, Marine Le Pen’s father, the National Rally has historically attracted men, both very young and very old, and been most notorious for the elder Le Pen’s Holocaust denial, hate crime accusations, and flirtations with Nazism. When Marine Le Pen took control of the party in 2011, she sought to change that image and professionalize the party. With her “de-demonization” strategy, she saw results fairly quickly: In 2014, the party began experiencing gains in municipal, regional, and European Parliament elections. Last year, the National Rally beat Macron’s party in elections for the European Parliament, riding a wave of anti-elite sentiment embodied by the Yellow Vest protest movement that rocked the country for months. The party’s 2018 name change was part of Le Pen’s larger strategy to distance herself from her father, whose reputation is seen as beyond salvageable. The presence of well-groomed students from elite universities, too, fits nicely into that strategy.

Everyone I interviewed differentiated Marine Le Pen’s party from the party of Jean-Marie Le Pen, accepting the National Rally’s former iteration as racist and anti-Semitic. Nevertheless, they also expressed blatantly nationalistic and Islamophobic views, remnants of Jean-Marie Le Pen’s party that remain hallmarks of the National Rally today. Just two years ago, the youth wing marked International Women’s Day by tweeting a meme that read, “Defending women’s rights is fighting against Islamism: The French woman is neither veiled nor submissive!” And last month, the National Rally launched a new campaign titled, “French, wake up!,” calling for security and justice in the face of “savagery” and promising to, among other things, increase prison capacity, apply zero tolerance, end “mass immigration,” reinstate mandatory minimums, and end social services for families of repeat juvenile offenders.

Studies posit a number of reasons why young people move further rightward: that they are searching for a sense of identity or purpose, that they follow friends or family into that ideology, that they come from authoritarian backgrounds, that they are the “losers of globalization,” left behind in an ever more interconnected global economy and susceptible to the radical right’s message.

But Rooduijn sees radical right parties gaining broader acceptance, gradually chipping away at the stigma surrounding them. “I think that the National Rally is a good example because you can really see when Marine Le Pen took over the leadership, she really changed the image of the party, trying to present the party as a party that you could vote for, a party that’s there for everyone,” he explained. “At the same time, when it comes to policy positions, to the actual ideas and the ideological base of the National Rally, nothing really changed. The party is still very radical when it comes to immigration. It’s still very radical on the European Union. It’s still very strict on law and order. It’s still very populist, meaning that it’s still very negative about all kinds of elites, most importantly the political elites…. So these parties have become more generally accepted. However, they have not really become less radical.”

These National Rally members highlight the ways in which some radical right activists and leaders stand apart from the average party voter, pitting their anti-elite, anti-establishment rhetoric against their desire to enter that establishment, hold power, and gain widespread respect—not to mention juxtaposing that rhetoric with their own impressive CVs.

For a long time, the party’s best known young member was Marion Maréchal, Le Pen’s niece. Hailed as the future of the National Rally, she became France’s youngest parliamentarian in modern history when she was elected to the National Assembly as a 22 year old in 2012. But her politics are more reminiscent of her grandfather, Jean-Marie, than her aunt—she honors the demons her aunt wishes to exorcise. After the disappointing 2017 election, she left the party and announced her exit from national politics; in 2018, she dropped Le Pen from her name. She was mentioned only once, in passing, by the young members I met.

“We wanted to do something and for me, it was this political engagement.”

These votes have names: There was Manon Bouquin, head of student life for Generation Nation and completing a Master’s degree in history at the Sorbonne when I met her in 2018. Growing up in Normandy, in northwestern France, she’d never had time for politics and her family wasn’t particularly political. “I never demonized the National Front,” she told me. “And when Marine Le Pen was denounced on television, I thought she was really courageous.” Then she moved to Paris and started university. Suddenly, she had time to think—and then came a series of terrorist attacks in 2015 and 2016, which triggered a “crisis of conscience” for her and a nationwide rise in Islamophobia and anti-Muslim attacks that continues today. (Some of the terrorist attacks occurred in Saint-Denis, the suburb where Ferreira went to school.) “It was really something for us Parisians. It was horrible at that time. We wanted to do something and for me, it was this political engagement,” Bouquin said.

There was Ugo Falcon, then a 19-year-old student at 3iS: International Institute for Image and Sound in Paris. His family wasn’t very political but they lived in Évry, south of Paris and home to Manuel Valls, a former prime minister for the center-left Socialist Party. So his parents supported the Socialists. “My first political impression was with Manuel Valls, whose discourse appealed to me for the most part—a discourse of the left,” he explained. “The National Front was pretty demonized by my parents, like nothing was worse than Le Pen. And when I was a child, I thought that was the case. And for a very long time, when people talked about the National Front, I said, ‘Yes, the National Front is awful. Marine is awful. Her dad is the worst.’”

Then there was Marc-Antoine Ponelle, studying law at University of Paris 2, who I interviewed when he was 22. He brought two fellow Generation Nation activists with him: Mike Boury, 20, was studying philosophy and law at the Sorbonne. Arthur Miège, who I’d first met a year earlier, during the 2017 election, was 19 and studying history at the Sorbonne. Boury and Miège were the only people I spoke to who said their parents also supported the National Rally. All three had once supported the center-right Republicans (formerly called Union for a Popular Movement).

For Ponelle, the ultimate decision to change parties came down to form, not substance. “I didn’t want to stay in a party of spectators. People would say, What are the current events? Look at what’s happening but not do anything. I think there are a lot of problems in France and I told myself that we can’t stay like that and just observe. It’s necessary to take action and it was the National Front that corresponded the most with my ideas.”

Éric B. was only 5 years old in 2002, but he still remembers the moment he first heard mention of the National Rally. That spring, Jean-Marie Le Pen shocked the world by capitalizing on the fracturing of the French left and qualifying for the second round of the presidential election, something the party wouldn’t do again until 2017. (French elections are spread over two weeks: a first round with many candidates on the ballot and then, assuming no candidate wins a majority of votes, a second round where the top two finishers face off.) But when he went up against the first-place candidate, Jacques Chirac, in the final round, he was coming up against not only Chirac but also a united “republican front” formed by both the left and right in an attempt to stop him in his tracks. Éric recalled his family contributing to that republican front.

He left school at 16 to work as a baker. Everyone else at work could talk about politics; he couldn’t follow. His formal education already over, the Internet became his teacher. He looked up all the political parties. He read Marx and Nietzsche. “I was very interested in the extreme left.” He paused. “That’s surprising.” He thinks he would have been considered a Trotskyite. He supported the New Anticapitalist Party.

The next step was attending a party meeting. “I don’t remember if it was about refugees or illegals in the building and police getting them out. And I went to this meeting and I was very disappointed because it was not really what I wanted in politics. It was a lot of dirty people screaming. And I was like, okay, that’s not really what I want. And then I really went in another direction.”

“Everybody took arms singing the Marseillaise. It was amazing. And then I began to be really interested.”

Éric found Le Pen’s speeches online and was intrigued. In 2015, he saw a post on her Facebook page calling on supporters to meet in Paris on May Day. He’d gone to one New Anticapitalist Party event. He figured it was only fair to go to one National Rally event. There, thirteen years after he’d watched his family members put aside their disparate opinions to join the republican front against Jean-Marie Le Pen, Éric cemented his interest in the National Rally. “I had no regrets. Everybody sang. Everybody took arms singing the Marseillaise. It was amazing. And then I began to be really interested.”

Éric told me this story in 2018, when he was the leader of Generation Nation’s Paris branch. (He once lost a job due to his political affiliation and agreed to speak on the condition that I only publish his last initial.) Among the Generation Nation members I interviewed, Éric stood out: He adhered more closely to the mold of a classic radical right supporter. His leadership position, however, allowed him insight into how the party was actively working to appeal to the other young activists I was meeting, who did not fit so neatly into that mold.

“A lot of young people unconsciously go to the left at first, but when they begin to work, begin to see the real problems of life—taxes, etcetera—they begin to change their minds,” he argued. “People have their little life, little apartment, have their dogs and the TV and a beer and have completely lost their minds. And that’s a real tragedy. If people are conscious of the problems, they generally vote for us. And when they listen to too much TV or to the mainstream media, they are completely brainwashed.”

“I think we attract [young people] today because we are anti-establishment, with the media, with the state,” he continued. He emphasized something Ponelle and others had brought up: taking action. “We are still active, almost every weekend on the streets giving out flyers or gluing posters, and a lot of parties don’t do that.” He also stressed the role of social media and how effectively Generation Nation engages young people online through memes and video content.

Organizing in Paris presents additional challenges. Bouquin, Generation Nation’s head of student life when we spoke, emphasized how the party works to appeal to young Parisians. “It’s more difficult here than in the provinces … because it’s a city with a very cosmopolitan culture,” Bouquin told me. “We have a following that is very working-class, who are workers, farmers, etcetera.” But, she said, “We’re a party that tries to adapt to the local issues. So in Paris, we don’t talk about agriculture, of course. We talk about pollution. We talk about ecology. We talk about problems with illegal immigrants. We talk about housing policies, social policies. In Brittany [a western region known for farming], we talk about agriculture.”

Young people, she said, “can have a fascination with responsibility,” and the National Rally is “a party that truly puts young people at the front,” showing them a clear path from joining to taking on more responsibility, doing media appearances, interacting with party leaders, and progressing to leadership roles or elected office.

The last time I saw Éric was in 2019, when the Yellow Vest protest movement was still going strong. He was thinking about how to channel that energy into National Rally votes in upcoming elections for the European Parliament. By then, Dussausaye, whom I’d met when he was leading Generation Nation, had progressed to a member of the party’s National Council. A year later, in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Ponelle, at 24 years old, represented the National Rally in municipal elections in Paris and became Generation Nation’s Secretary General, its second-highest position, while still pursuing a law degree. Boury, at age 22, represented the party in Valentigney, near the Swiss border in eastern France, in the same elections. Falcon, now 22, became the communications manager for the National Rally’s Val-de-Marne chapter, just south of Paris, and attends business school; he started a company that advises clients on digital communication. Éric is in charge of training activists in Generation Nation’s Île-de-France chapter, the region including Paris and its suburbs. And in those 2019 elections, then-23-year-old Jordan Bardella, who succeeded Dussausaye as the leader of Generation Nation, won a seat in the European Parliament. Now, at age 25, he is Marine Le Pen’s second in command and the party’s vice-president. Another political career nurtured at rapid speed by the National Rally’s youth wing, he is laying out a blueprint for the right-wing French youth queued up behind him.

[ad_2]

Source link