[ad_1]

This story was originally published on VICE Netherlands.

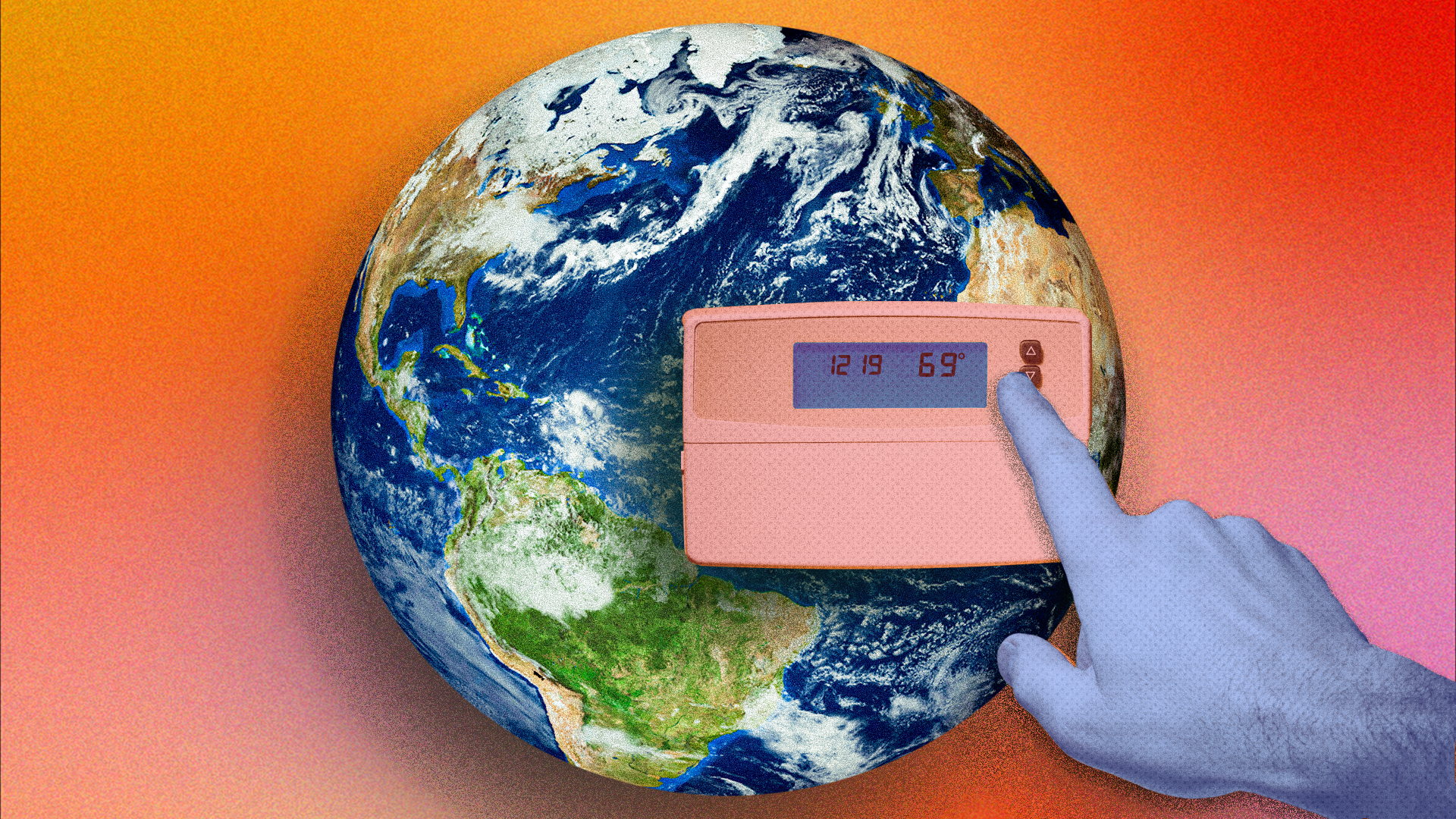

Scientists agree that we need to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius if we want to keep living on this planet. The Paris Climate Agreement, a historic 2015 decision that set concrete targets to fight climate change, has been signed by 197 nations. But these goals won’t meet themselves – the signatories will have to act immediately and drastically to cut carbon emissions by 2050.

Unfortunately, that’s easier said than done. According to the 2020 Climate Change Performance Index, there were “signs of a global turnaround in emissions” in 2019, but none of the 85 countries assessed were “on a path compatible with the Paris climate targets”. In plain words, no one is doing enough. Particularly worrisome were the performances of Australia, Saudi Arabia and, above all, the US, which replaced the gulf country in the worst performing spot.

The concept behind Carbon Dioxide Removal is to extract existing CO2 from our atmosphere. The CO2-rich air would have to be captured and filtered before being released. The extracted CO2 could then be pumped into empty North Sea gas fields and stored there. Another option would be to plant more CO2-absorbing trees or even algae, although scientists say this method would take too long.

Even though these techniques sound feasible, geoengineering is still pretty controversial among scientists. Both methods could have very unpredictable and potentially irreversible results. And yet, both governments and corporations currently include them in their future policy plans. A recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also incorporated CDR in all of its projections to keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius. To learn more about whether we should consider geoengineering a realistic option, we talked to four young experts on the topic.

Ina Möller, 31, PhD in Political Science at Lund University on the Emergent Politics of Geoengineering

I don’t think Solar Radiation Management will be put to use very soon because it requires decision making at an international level. However, Carbon Dioxide Removal will be implemented at a smaller scale, although there are currently no economic incentives to do so. We could capture CO2 and use it as a fuel, for instance, but storing it permanently isn’t profitable. And that’s what we’d need to do to reach negative emissions.

Highly polluting companies like Shell often include these techniques in their future projects to achieve carbon neutrality. That’s a problem because they’ve never been tried before so we have no idea whether they’ll work. It’s incredible that they exist, but we shouldn’t put our hopes in them. We should be acting like we don’t have these options.

Amy van Groot Battavé, 24, strategy consultant in the energy sector

The debate about CO2 capture has two sides. One argues we have to do everything in our power to reduce CO2 emissions. The other says that if we start doing this, we won’t go through with more sustainable projects. I understand that fear, but I don’t think it’s a reason to step away. I think climate change truly is a crisis and in times of crisis, you have to consider less-than-perfect solutions. It’s not like we have a lot of time left.

In parallel, we also have to go through a green transition. I think of geoengineering as a temporary solution. You can’t switch the entire system to green energy overnight. It’s important that the government creates incentives that will make investing in fully renewable energy sources more attractive in the long run.

Kevin Treu, 27, master’s student in environmental science at Wageningen University

Geoengineering could be used as an excuse. Companies will argue they can carry on with business as usual because in a few year’s time they’ll be able to suck CO2 out of the air. But what if it doesn’t happen? There are still too many unanswered questions to base our current strategies on these techniques. Even if they do work, we have to ask ourselves, “What problem does geoengineering really solve?” If we don’t change our economic system with its endless growth and consumption, we’ll end up right where we started.

I do think both Solar Radiation Management and Carbon Dioxide Removal will be used at some point. Global emissions have only gone up since the Paris Climate Agreement. Personally, I don’t think we’ll reach the goal of zero emissions in 2050. I hope I’m wrong about this, but I don’t think I am.

Alejandra Torres Rodrigues, 29, master’s student in Geo-Information Science at the University of Twente

Planting trees can’t be our only hope or policy measure. I worry about our forests being reduced to areas where CO2 is stored. A forest is much more valuable than that. You could plant many of the same fast-growing trees that can take in a lot of CO2, but that shouldn’t be the idea.

The issue with many geoengineering techniques is that people are waiting for smart technology to fix everything. At this point, we know it won’t work. We have to do something about the root cause of emissions. We also have to think about the social and economic consequences of using these techniques, so they don’t contribute to more inequality.

[ad_2]

Source link